By Doug Holder

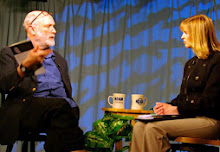

Luke Salisbury is a professor of English at Bunker Hill Community College in Boston. Salisbury, 60, is a man with a gift for gab, and the well-turned phrase. Eclectic in his tastes, Salisbury, with his signature rapid - fire cadence and disarming laugh, regales you with his anecdotes, his impressive knowledge of baseball, and his “alternative” universe of film, books and political intrigue he has spent many years pondering and writing about. He is the author of a number of fiction titles including: “The Answer is Baseball.” (Time Books, 1989), “The Cleveland Indian” (Smith, 1992), and his novel about the great filmmaker D.W. Griffith “Hollywood and Sunset” (2007). His writing has appeared in such publications as “The Boston Globe,” “Ploughshares,” “Cooperstown Review,” "Pulp- smith,” and others. Salisbury received his M.A. in Creative Writing from Boston University and lives in Chelsea, Mass. with his wife Barbara. I interviewed Salisbury on my Somerville Community Access TV show ‘Poet to Poet/ Writer to Writer.”

Doug Holder: You said the dawn of Elvis, the Beatles, liberated you from the buttoned-down, all boys purgatory, prep school world you grew up in. Who were the writers that liberated you when you were coming of age?

Luke Salisbury: I went away to an all boy’s school when I was fourteen. I hadn’t been a big star with girls in the 7th and 8th grade. I felt I was isolated. I felt that I was never going to get off. There were things that kept my soul together: rock ‘n roll, literature, and baseball. My life was changed—saved or ruined—when I read the “ The Great Gatsby” when I was seventeen. I never wanted to do anything but write a book that good. I never will; maybe no one else will. The book explains even in the first page the whole world. Its pressures, its nuances, its mystery. Faulkner would be another influence. Why? Because there is something about being a teenager reading something you can barely understand, and you know it is over your head—but by God—you know it is worthwhile.

DH: Did you feel liberated by any 60’s era writers?

LS: I got that from rock ‘n roll, not from 60’s literature. I was not a Jack Kerouac person. I was not reading that stuff as it was being done. Later in the 60’s when I really needed to be on an island protected from my own demons and the demons around me, Nabokov became my obsession. I was traveling around Europe in the summer of 1968 buying his paperbacks at kiosks in railroad stations .I was always in an alternative world of baseball, literature and rock ’n roll. I’d love to name some 60’s poets but none of them were important as the “Rolling Stones.” And also what I considered classic literature. In the 60’s I spent a long time reading “Tristan Shandy” and “Tom Jones.”

DH: Did you engage in any of the “excesses” of the era?

LS: As many as I could. But there were three things going on. Political revolution which I thought was bullshit because I didn’t actually see anyone go out and fighting. Then there was the drug revolution. I always thought I was wrapped a little too tight to do the heavy duty stuff. Then there was the sexual revolution. It was a wonderful time to be a young man. I mean the middle and late 60’s, not the stuff that comes to us post “Easy Rider.” Love and peace that stuff was bullshit. It was about resistance. It was about resisting the draft and authority.

DH: You wrote two assasination novels. One was “Blue Eden.” Did you find the elitist intrigue, the possibilities of nefarious cabals behind the Kennedy assassination a source of fascination?

LS: It was. Because in the late 60’s I’d sit around and think about the novels I would like to write. I became obsessed with the Kennedy assassination. This stuff happens in front of your face, you don’t know what it is. There is subtext, there are stories… this is raw material. Everybody was taking a crack at it—the big time writers like like Mailer and DeLillo. But once you get into it you can’t get out.

DH: So who really killed Kennedy?

LS: I have no idea. Maybe Oswald, but he certainly wasn’t alone. It’s fascinating but it is like drugs and then you go home to detox and get out.

DH: In a recent book you penned “Hollywood and Sunset” you write of D.W. Griffith, the famed filmmaker, whose signature work was “The Birth of a Nation.” You refer to Griffith and others of his ilk as “sellers of light.” What are novelist’s sellers of?

LS: Ah… Inner light. All sorts of light. I got interested in Hollywood because it is really the center of power.

Basically D.W. Griffith invented Hollywood. He did everything with the two dimensional movie that could be done. He made the most racist movie ever produced: “The Birth of a Nation.” It made a huge amount of money and it took advantage of a racist sensibility of the time- what could be more American?

You had a frontier of the movies in his time. What happens when America hits the Pacific? We invent a dream-factory Hollywood. So I became very interested.

DH: How does this American sensibility differ from the European?

LS: “We” have to keep moving. We never stop. The past is used up.

DH: Does obsession help a writer?

LS: Yes. Who the hell is willing to sit and write a novel and then another novel, without it getting published? If they finally do get published the only people who read them is an obscure reviewer somewhere. But you keep doing it. It is madness. Poets can write a poem in five minutes or five years. There is no way to do this as a novelist.

Someone has to support you; or you have to support yourself. Many of us teach. So yes obsession helps. But just having obsession doesn’t mean that God will give you success, or that you have much talent. But it makes life worth living.

DH: Many writers work a variety of odd jobs to support themselves. You worked as a security guard for a number of years. How did that help or hinder your writing life?

LS: While I was a security guard I read “Gravity’s Rainbow,” and “Remembrances of Things Past.” I worked at Polaroid during the night shift. You have to survive if you are a writer. Especially if you are not in the generous bosom of a university. Faulkner said the best job for a writer is a piano player at a bordello. The hours are good and there is a lot of interesting company around.

I had many jobs in the 70’s. I worked in the Welfare Dept.. I worked for a school board in the Bronx, etc…

DH: You have taught at Bunker Hill Community College for over twenty years. How has this been?

LS: I have taught for 22 years. And it’s a great job. The average of the students is 30 years old. People come from everywhere, and there are no Yuppies. This isn’t Boston University. The kids and older people don’t think I am an idiot because I don’t make much money. Most of the students at Bunker Hill are there to learn skills, learn English, etc… I don’t think you can do better teaching adults in a public school, in a big city. It’s not the hell-hole that “Goodwill Hunting” characterized it as.

DH: You have been published by Harry Smith the legendary small press figure.

LS: Yes. Harry was basically a poet and published poets. He had a magazine from 1964 to 1998 “The Smith.” He had a policy of publishing unpublished writers. Half the magazine was devoted to their work. I had sent him something in 1970 and he turned it down. Five years later I sent him something and he sent me back an envelope with a “Yes” written across the front. He discovered me, and my friend the poet Jared Smith. He help start COSMEP—the seminal small press organization.

DH: So you have an affinity for the small press?

LS: Oh yes. There would be a lot less literature if it wasn’t for the small press. Where do we go if we are not one of the twenty people writing novels? I thank God for the small press and the internet—we can find each other here.

DH: You have written extensively about baseball. Why?

LS: You get a tremendous amount of respect knowing about sports. Baseball was that ‘alternative” world for me—it saved me.

Doug Holder