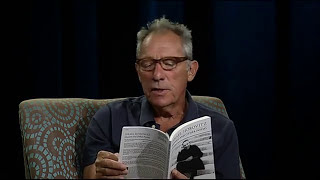

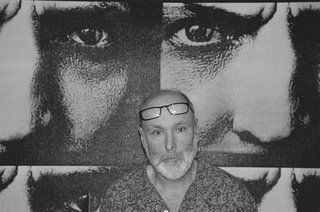

Fred Marchant: A Happy Person: A Turbulent Poet

Poet Fred Marchant is not stingy with a smile, or the hail-fellow-well met. He is a gracious and thoughtful subject for an interview. Although Marchant told me he is a happy person, he said there is turbulence in his life and in his poetry. He describes his new collection of poetry from the Graywolf Press "The Looking House" as having many poems that can only be described as harsh.

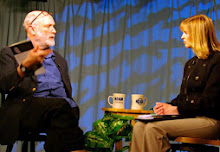

Marchant has a considerable number of accomplishments under his belt. He is the editor of “Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford, 1937-1947,” as well as being the author of four books of poetry, the most recent: "The Looking House" from Graywolf Press. Marchant teaches at Suffolk University in Boston, and founded the Suffolk University Poetry Center. He has been a recipient of fellowships from the Ucross Foundation, the Yaddo Foundation, and the McDowell Colony. I talked with him on my Somerville Community Access TV Show: "Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer."

Doug Holder: William Stafford was a conscientious objector during World War 2, you were during the Vietnam War, is this in some way the reason you were attracted to his work?

Fred Marchant: Yes. As a ground level truth. I knew his poetry before I knew the biographical fact. But when I read that biographical fact it amplified his poetry and it made more sense. And then over the years it has meant a lot to me. Not that he was much in the way of talking about his C.O. experience. He wrote about it in prose as part of his Master’s thesis at the University of Kansas.

DH: He started writing poetry late?

FM: Well- because of the war. Yes and no. He started as a graduate student. Then the war intervened. And during the war he was in the Civilian Public Service. CPS was a middle ground between going in as a non-combatant, or resisting outright and going to jail. It was alternative service. It was typically in the wilderness. It was in remote places. I studied with Stafford and we became corresponding friends. He was the first poet that I brought to Suffolk University in Boston. The Creative Writing Program began with this first writer. He passed in 1993 and his son edited and selected his New and Selected Poems (Graywolf Press). He connected with me a few years ago. I was approached by the son and Graywolf to write his biography. So I went out to the archives in Portland, Oregon. But I decided I was getting on in years and felt that a biographer should be younger. I needed to write my own poems. I thought that Stafford would approve of that decision. But as I was leaving the archives I thought I would like to write an essay about his early poems that I discovered. I was given a Xerox of his first ten years from his file. There were 400 poems. I thought a third of them should be read. They weren’t available anywhere. Through the editing process I was trying to understand his C.O. experience and how it reflected on mine.

DH: In an interview with Stafford he states: "I keep following this sort of hidden river of my life. You know, whatever the topic or impulse which comes, I follow it along trustingly. And I don't have any sense of it coming to an end, or crescendo, or it petering out. It is just going steadily along."

FM: I would like that to be case. Bill Stafford seems to have a calm direct access—more than I do. I am more or less a turbulent person. I’m a happy person, but turbulent none-the-less. There is serenity to his poetry. There is an effort to create a peaceful relation with his world. It meant paying attention to the way things are speaking to him. There is a good part of myself that has an allegiance to that. I also feel that that I am much more a struggler. I do need to that dialectical back and forth. The point of convergence is that I understand the virtue of the sustained writing process.

Stafford would wake up at 4 or 5 in the morning everyday to write. I can't say that I am able to do that. But I do know that I am at my best when I am writing regularly.

DH: You have been an editor at GRAYWOLF PRESS, a prominent small press for a number of years. Small presses are essential venues for emerging poets to established ones. Have the small literary presses been good for you?

FM: I write very slowly. I revise. I am a gradualist. Every small press gesture or commentary has been a gift. I was 46 years old when my first book of poetry came out. I wasn't a kid, but I was still a young poet. I can say the small press has saved my life in terms of writing. If you really take a stern look at recent American capitalism, the small press operates under the assumption that this is really not for profit. It is really for the art, for the culture, or the circulation of things in that order. I think there is something spiritually profound in that fact. Non-profit may be the business model for sustaining literature.

DH: You got your PhD from the University of Chicago in the 70's. What was the academy like then?

FM: I was in a program called: "The Committee on Social Thought." It was a group of philosopher, social scientist and literary folks. The reason I applied there was that Saul Bellow was teaching. I read Bellow's novels and I knew there was a kind of wisdom there that I was very interested in. Bellow was my thesis advisor. The reason why he was good is that he wasn't the ordinary academic. I was an ordinary graduate student. I thrived in the fact that he gave me a great deal of independence. He had a lot of ambition on my behalf. Some of the projects he proposed were beyond my capability at the time.

DH: I love Bellow; I started out with his novel "The Dangling Man." I heard that he was a real character.

FM: I don't think he was a character. I think he liked to make people think he was a character. I felt he was a day to day artist. His daily practice was writing. And when he wasn't writing he was reading. There was a great openness.

I remember visiting him once at his apartment for a conference about my thesis. I forgot which novel he was working on. But when he was working on a novel he had large notebooks, but he also had stacks of books he was reading. And I noticed he was reading the letters of Wallace Stevens. I don't know if this is a fact, but I think he's got some characters that are woven out of the kind of figure that Wallace Steven's conveys in his letters.

DH: Ilya Kaminsky wrote in a blurb of your book: "In a time of lies and mediocre ironies in literature, here is a voice that is never afraid to say what matters." What do you think is meant by mediocre ironies?

FM: I'll make my guess. There is a kind of irony that's basically self-protected--keeping things at a distance--not letting you be open or vulnerable to things that are truly hurtful. One of the ways of coping with this in our society is to be ironic about it. There is a distance that is created. Irony is a deeper resource than that. It stems from a broken sense of the world.

DH: In your latest collection: "The Looking House"(Graywolf Press) your poem "Pickney Street" captures the fleeting beauty of a street, on Beacon Hill in Boston.

Pinckney Street

A view from the crest of Boston to the river--

a walk and my friend stopping to say that

for three weeks each year

and beginning tomorrow

this will be the most

beautiful place in the city--

our respite in the brick-faced buildings

blushing in sunlight,

in star magnolias swelling,

about to burst into bright badges,

medallions of tangible life and light

the shook foil that Hopkins wrote about--

the minutes we have of granduer, hope, gratitude.

You refer to Gerald Manley Hopkins who wrote of the granduer of life: "It will flame out like shining from foil...”

Do you think this is the job of the poet to remind the reader that the flame will be a burning ember so carpe diem?

FM: I will say this about that poem. It has fragility to it. It is a poem that is fully aware that all this is ephemeral. On the other hand, just because it is ephemeral doesn't mean it we have to mourn. Of course mourning is part of life. The poems in this book are quite harsh. This poem was intended to soothe. The poem has a gentle affirmation of the pleasure of recognizing the granduer of things. I think we should all take pleasure in the granduer of things.