I want to share this essay from small press poet Don Winter. I became acquainted with Don through a magazine he was a contributing editor to " Fight These Bastards." I had a couple of reviews in the journal and I became familiar with his visceral, and evocative work.

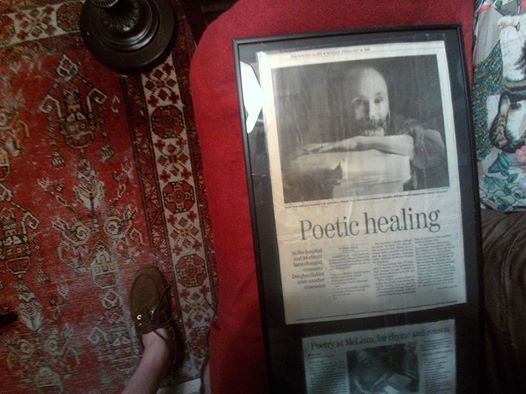

From 1999-2008, Don Winter’s poems appeared in most small press (and many “academic” press) journals. Small Press Review called him “One of the best poets in [the] small press.” Working Stiff Press released Saturday Night Desperate: A Retrospective, 1999-2008, in August 2009.

Don has taken a break from the poetry world, but I can only hope he will reappear.

“One of the most trenchant, insightful overviews of American Poetry ever written.”---Small Press Review

Press of the Real: Poetry of the Working Class

By Don Winter

Working class is. It is the vast majority of us in America “who must live by the sale of [our] labor power, and [who] have no other life sustaining forces” (Line Break 12). It is those of us who perform jobs that seem boring, routine, banal, trivial, pointless, who as sociologist George Ritzer points out, “do the same thing every day. It is boring, it is bad, it is dehumanizing, but the green stuff seems to alleviate the boredom, at least once a week” (47). It is the man who worked at the power plant in Jack London’s John Barleycorn. It is those who labored in Charles Bukowski’s Post Office, “people who were caught in traps…They felt their lives were being wasted. And they were right” (142). It is the man and woman in James Scully’s “Enough.” It is those who suffer jobs destructive to human existence, jobs underscored by the ideology of Frederick Taylor’s Scientific Management, which has gained force in recent years, driving the expansion of the post-industrial service and information economy: jobs in consumer services, adjuncting, wholesale, and retail. It is those displaced industrial workers who must endure forced entry into the lowest levels of that service economy: jobs in domestic, food service, clerical, and telemarketing (Coles & Oresick xvii).

In Niles, Michigan, the working class town where I grew up, you were educated (euphemism for “socially managed”) for docility: conformity to the rules, obedience to authority, and receptivity to rote learning. Spontaneity and creativity were not rewarded. Niles High School produced submissive, malleable adults who were eager for jobs that would set the schedule. A good job meant Clark Equipment Company, or Simplicity Pattern, or National Standard. Work became the fabric of life, providing for a family the work ethic. That work ethic, the working class ethic, prized the functional and the practical. Conversation was direct, sometimes blunt, purposeful, but not reflective, and truthful, but you kept that truth in the family. You learned to laugh to survive; you passed on stories of family and town history, you passed on your values. Often you felt rage, bitterness and denial at being exploited by those you could not even name. You had difficulty in seeing multiple perspectives, but you felt others should be treated fairly, so you stood up for the “little guy.” And at home you made do, you sacrificed, you supported each other. Patriarchy ruled home, ruled the workplace. Often violence exploded in both. Education was fine, as long as you didn’t get too much of it, as long as you didn’t forget “where you came from.”

No, that’s not quite. Resistance to willed amnesia is a myth. You wanted to rise, through the accumulation of money and its power, above who you are and where you began, and then to marginalize, obscure, silence that beginning. But without intergenerational money, upon which middle class society rests, most settled for upwardly mobile versions of themselves predicated upon a pyramid of consumption, formulated not so much on the need for a particular object as the desire to own it to distinguish themselves socially: the idea that a Mercedes is a status symbol that places you above the one who owns a Volkswagen, even though you may be a paycheck or two away from homelessness. As Linda McCarriston notes:

Analysis of class in America is approached by different thinkers with

different standards of measure, but it’s safe to say that status—objects, jobs,

reputations—is not the same as class. Take Thomas McGrath dying in a

single room in Minnesota with a black mitten on the hand that could never

get warm after the VA surgery on it, a handful of books around him. He

NEVER was middle class. But he was educated, brilliant, and famous. The

academy threw him out and McCarthy—which should concern us all today—

finished him off. People are called, and call themselves, middle class when

they have no safety net beyond the next paycheck, no leisure in which to

learn and reflect upon their fate, no job security, no secure medical (and

dental, of course). What they have is an education and enculturation in which

they’ve learned to look down their noses at themselves “before,” in their

past notions of a life

The first lines I wrote, at age 40, evidenced some of the rage, bitterness, and denial I felt in my working class poor life: “For years the land worked us, planned/ our cities like shotgun blasts.” Plain spoken, private lines I wrote sitting on a bar stool in Niles. Here in my first attempt, in many ways brute, “snake brain” writing (I had no critical terminology to describe what I wrote), there is inner will, inner power, and social vision—also that rage—of a worker who realizes he is of a larger group that is, by-and-large- exploited, and who refuses to be silenced, to be extinguished. In the books I’d begun to read, such as The Branch Will Not Break; To Bedlam and Part Way Back; Not this Pig; Chicago Poems; Ariel; American Primitive; What Thou Lovest Well, Remains American; I discerned a reticence about the working life. I mean, there were a few Levine work poems, and several of Frost’s. And of course Sandburg’s, but as Williams observed in a letter to Moore, Sandburg’s “work” poems are a “drift of people, a nameless drift for the most part.” Why was it that poems from the position of the working class poor, from that life and that labor being economically exploited, seemed to not be a powerful strand in American Poetry? Why was the voice of a defined social class—whose condition has long been the subject of study by sociologists and political scientists—as absent or misrepresented in American “academic” poetry, as that of African-Americans had been until recently?

There is, and has been, the resistance of the “academic” literary canon to “those below,” certainly those of the working class. I believe this resistance arises out of a failure to appreciate, or react against, the class content of the poetry. That there isn’t a clearer concept of the “working class” is a big issue. Why can’t I justify my working class poems in the “academic” environment? Largely because the working class environment and real voice lack the political, social, and economic naming that might make them dynamic. Rarely gathered together as a locus of critique, the elements of a sociological poetics uncover the terms and uses of most “literary theories” as taxonomies of taste and/or group identity, joustings for a higher rung on the status ladder. And there simply is no cogent “working class” theory. The project of trying to place the importance of poetry in my life as a writer of poems becomes problematic as I realize how antipathetic to my poetic the “norm” is, and how few, scattered, and out of print are the theoretical materials I need to defend and articulate it. There is in American “academic” poetry a poetry of the “working class” that is all costume and no content. Most “working class” work that is acceptable to the digestion of the American “academic” poetry norm is not politically conscious. It’s nostalgic, romantic, soft focus. Anybody can sling dialect and dress his or her speaker in denim or leather or rags. Much of what American “academic” poetry loves as “working class” and “poor” is voyeuristic. So to situate the importance of poetry in my life as a writer of poems is to point to this dominant academic tradition (normalizing discourse) AND the (my) dissident tradition, both ever present and in dialogue, though the “dominant” tradition avails itself of the false prerogative of refusing to talk with its other as equal.

Dominant tradition be damned, I knew when I began to write I wanted to embrace, not exclude, the working class poor in my hometown. I wanted to express and claim my belonging, my sameness to them. I felt that in traveling to the deepest parts of myself, and my experiences in the localisms of Niles, in other words the particulars of my working class experience, I might touch the deepest parts of the working poor in Niles, and elsewhere. My exemplars, McGrath, Scully, Boland, and McCarriston, as well as Charles Bukowski, Phillip Levine, and Gerald Locklin, are radically awake in their writing, something any poet should aspire to, quaky-kneed beginner or experienced connoisseur, with a consciousness fiercely engaged by the particularity of this world, peddling hard as it can to attend to and honor each moment in that relentless flood of disparate sensations, experiences (and memories about sensations and experiences), and ideas which is contemporary life; and they write with an authority of voice rarely achieved by either man or woman. They have begun, along with writers like Jim Daniels and Fred Voss, to clear a space in American poetics where “forbidden voices” such as mine can exist and persist as an urgent place for utterance of consciousness, to speak for my class as well as myself, a poem of self “made valid for all” (des Pres 164). They have not forgotten their class, in fact have become bards for it, and they have been taken seriously.

Works cited

Bukowski, Charles. Post Office. California: Ecco Press, 1980.

Coles, Nicholas, and Peter Oresick, eds. For A Living: The Poetry of Work. Chicago:

University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Des Pres, Terrence. Praises and Dispraises: Poetry and Politics, the 20th Century.

New York: Penguin Press, 1989.

Ritzer, George. The McDonaldization of American Society. Arkansas: Pine Forge Press,

1988.

Scully, James. Line Break: Poetry as Social Practice. Seattle: Bay Press, 1988.

Taylor, Frederick W. The Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Harper &

Row, 1947.