Oppressive Light

Selected poems by Robert Walser

Translated & Edited by Daniele Pantano

Black Lawrence Press

ISBN: 978-1-936873-17-3

180 Pages

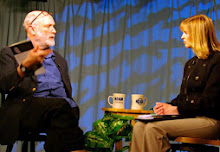

Review by Dennis Daly

“I’m not here to write, I’m here to be mad,” Robert Walser (1878-1956)

explained to a friend and admirer who had come to see him at the Herisau asylum

in Switzerland. Walser meant it. For the next twenty plus years until his death

this famous novelist, short story writer, and self-described poet refrained

from writing anything at all. Most who knew Walser best before he entered the

asylum thought him mad. Those who visited him after he was committed believed

him quite sane. It seems to me that there is a lesson here—somewhere.

As a young man Walser got himself a job as a bank clerk, a job he was

very good at and clearly identified with. He later failed at an acting

audition, worked at multiple clerical jobs, and trained as a butler, at which

he worked and seemed suited to. His little view of the good life, where details

are ordered, and emotions are calm, probably stems from these experiences.

For a time Walser even supported himself with his writings. Franz

Kafka, for one, delighted in his prose and echoed Walser in his own writings.

Hermann Hesse also admired Walser’s art.

But after the First World War Walser’s writings became less popular and

he turned into a vagabond of sorts, moving from place to place. He had a

position in the National Archives in Bern for a while, but then was fired. He

drank too often and too much and finally tried suicide, an attempt which he

also numbered among his perceived failures.

During these years Walser wrote some excellent expressionistic poems.

Many of these unique, well-crafted miniature pieces were published in

prestigious literary magazines. Walser’s madness, if madness it was, did not

originate in artistic anonymity or lack of acknowledgement. It came from some

place deeper.

Danielo Pantano, himself a Swiss poet, does admirable work in conveying

the intensity and starkness of Walser’s darkly euphoric vision. The original

German is printed on the opposite pages for those interested in Walser’s rhyme

schemes and other mechanics translated into this nicely toned English version.

The first poem in the book, entitled In The Office, entrances with the

portrayal of everyman- the- clerk. It’s not a caricature; it’s something else.

Reading it is like observing the pinning of a butterfly: intimate and

troubling. Here is the better part of the poem,

The moon peers in on us.

He sees me as a miserable clerk

languishing under the strict gaze

of my boss.

Embarrassed, I scratch my neck.

I’ve never known

life’s lasting sunshine.

My flaw is my skill…

Notice also that it’s the moon that observes the clerk in the above

poem. We get to watch many of Walser’s poetic creations from above, from outer

space. In the poem Rushing we look down on the dynamic of Walser’s world. The

poet says,

In the world there’s still this rush,

the rush that never ceases;

I love—and it will never stop,

a love that rushes through the world.

Sometimes the poet zooms in for a closer look. In the truly miniature

piece, As Always, a simple lamp and table seem to have the same weight as the

poet’s longings and fears. These juxtapositions all take place in a single

room, yet strangely there doesn’t seem to be a whit of claustrophobia. Walser

describes the scene and ponders,

The lamp is still here,

the table is also still her,

and I’m still in the room,

and my longings, ah,

still sighs, as always.

Cowardice, are you still here?

and Lie, you, too?

I hear a dim, Yes:

Misfortune is still here,

and I’m still in the room,

as always.

Walser often uses the idea of outside meadow and or inside room as

geographical points, places of safety where he can demand a kind of sanctuary

from nature. One of his most existential poems and one that uses both these

geographical havens the poet calls Tryst.

Here are two sections,

…the meadows are fresh and pure,

and a spot in shade and sunshine

like well-behaved children.

Here the strong desire

that is my life dissolves,

And,

… there’s complaining in the room

of such a soft kind, so white, so dreamy,

and again I’m left knowing nothing.

I only know that it’s quiet here,

stripped of all needs and doings,

here it feels good, here I can rest,

for no time measures my time.

The macrocosmic world seems to be hiding something from human kind. In

Evening Song the poet hints at it this way,

Something like the weariness of nature

wants to lie down on the houses and fields.

Its subtle smile moves from tree to tree

but you can barely recognize it.

How miserable is the small breeze

that still travels the evening world.

Certain poets by their withdrawal from social and emotional life negate

themselves and almost disappear. As they vanish their vision becomes their

existence and its intensity becomes overwhelming and even oppressive. It

empties them. They become cold, husks of themselves, the remnants left after

poetic possession has finished with them. The young Walser somehow knew this.

One of his early poems describes the scene,

You do not see me crossing the meadow

stiff and dead from the mist?

I long for that home,

that home that I never had,

and without any hope

that I’ll ever be able to reach it.

For such a home, never touched,

I carry that longing that will

never die, like that meadow dies

stiff and dead from the mist.

You do see me crossing it, full of dread?

On Christmas Day in 1956 a group of children found Walser’s body,

frozen stiff, lying dead in the snow. He had walked away from the asylum,

across a large meadow, leaving footprints. Those footprints are here in this

book.