|

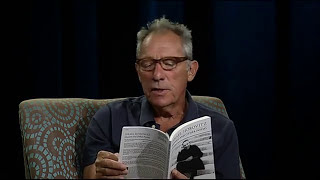

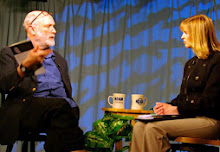

| ( Left to right) Dan Tobin, Alex Green, Jean Houlihan, Michael Todd Steffen (back) Fred Marchant, Doug Holder |

Seamus Heaney Tribute: Appreciation and Reflections

By Alice Weiss

On

Wednesday the 27th of August, along, I attended a tribute to the

Irish poet, Seamus Heaney, deceased one year.

It was organized and presented by Michael Todd Steffen at the Hastings

room, First Church Cambridge. We were in a small yellow painted room. The

furniture, pushed aside for folding chairs was plush and there were paintings

on the walls in ornate frames, or at least that’s how I remember it. The

podium was set in front of a mantel. The weather played a part. It rained and

thundered. I had not given much

attention to Heaney’s poetry. After this

evening that changed. The essay that

follows reflects my memories of the evening and readings I did and thought

about in response to it.

Presenters

included two Irish-American poets, Joan Houlihan and Dan Tobin; the

Jewish-American poet and cultural entrepreneur, Doug Holder; Back Pages in

Waltham bookseller and publisher, Alex Green, and Fred Marchand, poet, war

resister, and Suffolk University emeritus professor of poetry. They all read and commented on a Heaney poem

and, except for Alex Green, read work of their own. Michael Todd Steffen made the introductions.

Steffen

began with a discussion of the Heaney’s poetry, took firmly into the high

territory of great poetry, but there was one poem, title actually, that struck

me especially, “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.” It’s slangy, calls up living in an occupied

Ireland and, it catches some truth about the concentrated code we call poetry. The poem, itself, is a bracing referential

meditation (if so languorous a word can be applied to the tartness of its tone)

on “the Irish thing’”and how people talk about it. Take the opening quatrains

of section III, its disgust with a public language rendered powerless by its

refusal to take sides and its burst into an impatience that nonetheless

maintains a ‘tight gag.”

‘Religion’s never mentioned here,’

of course.

‘You know them by their eyes,’ and

‘hold your tongue.’

‘One side’s as bad as the other,’

never worse,

Christ, it’s near time that some

small leak was sprung

In the great dykes the Dutchman made

To dam the dangerous tide that

following Seamus.

How do you talk through a mouth gag that makes you ignore

history? some small leak? The poem apes

the language of the op-ed in such a way that it never leaves a question

about where its heart is. An unending

dilemma hovers, though, in the poem, and finally breaks out in the last

stanza: like Paul Celan, and Adrienne Rich, if he was going

to sing he had to do it in the language of his oppressors.

Ulster was British, but with no

rights on

the English lyric: all around us,

though

We hadn’t named it, the ministry of

fear.

Michael, introducing Doug

Holder, admitted that he had intended to feature only Irish- American poets,

but then, Doug. Not a word else was

needed. If there was anymore said I

didn’t hear it because I was laughing.

The room, I must add, was quite hot and someone handed out little

personal fans. They looked like the

paddles art auction houses provide for bidders.

Doug, of course had his opportunity and thanked all the fans in the

room. People hissed, I called out “Sit

down” Joan Houlihan laughed.

Doug read

Heaney’s, “The Frontier of Writing,” and bumped us out of laughter back into

that landscape of hostile occupation that was (is?) Northern Ireland. Except here, the “tightness and the nilness,”

that one attempting to cross a border (frontier) feels when stopped and inspected

at gun point, has more to do with the hesitations and fears approaching the act

of writing, subjugating that resistant part of your inner self to glide

obediently past them,

out

between

the posted soldiers flowing and

receding

like tree shadows into the polished

windscreen.

Whether internal or external trouble always looks like

British soldiers.

Doug’s

poems too explored an inner/outer landscape.

His was Bickford’s, in “Eating grief at 3 A.M,” dedicated to Alan

Ginsberg and evoking Walt Whitman at the supermarket old Marxists, flirting old

ladies, a landscape, this time of loss leaving the poet with no place to sit. In another of his poems “You know it

is tough being a writer,” Holder managed to chime both Seamus Heaney and Henny

Youngman: “The waiter /Charging me extra/ For the fly in /My soup.. . . And

take my creative partner/Please.” This

swing between the world of Take-my-wife, and Northern Ireland seemed apt. It

provided urban levity for all the rural seriousness you knew was coming.

Joan Houlihan read Seamus Heaney’s

“Miracle,” a poem drawn she told us from the New Testament where a man, unable

to walk, was brought on a stretcher to Jesus to be healed. The crowd was

such that his friends could not get through with their stretcher and so climbed

on the roof, pried off parts of it and lowered the man down. Heaney’s

poem, she explained, had its origin in the days when he had suffered a stroke

and he was able to recover, but only help from the orderlies, the EMTS, the

night nurses, in short, the hospital community. Her own son had had a brain

injury, she added, and she knew what it was to depend on a caring community responding

strangers.

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in –

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in –

Their

shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let up

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let up

Until he’s strapped on tight, made tiltable

and

raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

For

the burn of the paid out ropes to cool,

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those who had known him all along.

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those who had known him all along.

In the

poems Joan read from her own work, a character suffering locked-in syndrome

survives with the

help of “the ones who had known him all along.” Using the strange feelingful language in “The Us,” and “The Ay,” her recent poetry of

wild almost celtic invention: an imaginary tribe, speaking an unexpected

language her poems too invoke the bare, quiet human interaction of caring.

and brae would spoon the broth,

and make talk between us

where mine own had gone,

as sounding saved by water,

rivered in its mouth

when saving ay had none

and all mine days were silt

and through the hand.

“Sounding

saved by water/ rivered in its mouth.” I understand this with my physical

center: sounding (the capacity of make sounds)(but also water itself as

in Long island sound, or measuring depths) saved by water, and then back

to language as river, incredible. I find

the same mystery in, for example, Heaney’s “Markings.”

iii

All these things entered you

As if they were both the door and what came through it.

They marked the spot, marked time and held it open.

A mower parted the bronze sea of corn.

A windlass hauled the center out of water.

Two men with a cross-cut kept it swimming

Into a felled beech backwards and forwards

So that they seemed to row the steady earth.

It seemed to me that Daniel Tobin’s

presentation also looked at ways Heaney explored the entering of things, “As if

they were both the door and what came through it.” Tobin read from his own study, Passage to the Center, Imagination and the Sacred in the Poetry of

Seamus Heaney.

Heaney’s quest demands that he explore the process of

self definition by tracing through his art the formative experiences that

helped mold his identity. . . .[It}

entails a paradox in which the very outward movement of the quest calls for a

radical inward scrutiny, an interrogation into the origins of the self.

As if you could not separate that

quest from the character of the man, Tobin spoke about his special capacity for

encouragement. Here is where Heaney’s

exceptional capacity to locate the self in movement towards others illuminates

the sources of poetry in ritual, More

than just a bunch of chants, ritual is a way for the self to merge with others. In Station

Island which I turned to in response to Tobin’s discussion, I found poems which explore that “merging” in its most

extreme form, as a mystical union with a landscape of “hard lodgings.” So these last lines from “Sweeney’s Lament

on Ailsa Craig”

But to have ended up

lamenting here

on Ailsa Craig

A hard station!

Ailsa Craig,

the seagulls home,

God know it is

hard lodgings.

Ailsa Craig,

bell-shaped rock,

reaching sky high,

snout in the sea—

it hard-beaked,

me seasoned and scraggy:

We mated like a couple

of hard- shanked cranes.

Picking up the exploration of ritual

and community, Tobin read his own work,

The Narrows, a ghazal, “A Mosque in Brooklyn,” It takes place in the basement of the

apartment house he grew up in. The poem

does a stunning turn with the word history,

There is no prayer that can abolish history,

though in this basement mosque the muezzin’s history

gathers in his throat like a tenor’s aria

and he calls to God to put an end to history. . .

Allah, Allah—above

the crowded rowhouse roofs.

Their rusted antennas, stalled arrows of history. . .

. . .these prayers are lifted on the thermals of history,

and sound strangely like. . .

the remnant who

survived a blighted history,

. . .lost themselves, flourishing into the One

without division, without names, without history.

The ghazal form

gives him an opportunity to endow the word history, also a concern of Heaney’s,

with a repetitive force which ends up turning on the notion of history itself.

The ritual takes the one step further, and by gathering in the throat of the

muezzin puts an end to it, history.

As the last reader, Fred Marchand, went right to the point: the impact of

reading Heaney on his own writing. He spoke of a time he felt that he could no

longer hear the music in his own poems and had stumbled upon a poem by Heaney

called “The Loose Box” and, it was implied, shook his deafness off. I found it a long poem to listen to, but

later read it from the New York Times

Archives. It’s a poet’s poem. A “loose box” is a high horse stall that

has four walls that horses are placed in so they can be held without

harnesses. The poem is in three

parts. The first lines of each section

place the source of a particular diction the poet has used throughout his career, then bursts

into that very language to describe an imaginative encounter using it. It’s an ars poetica: Heaney openly exploring the

sources of his own poetic language. The

sections of the poem seem disjointed , but the question is implicit in each of

them:

talk about the properties of land,

the actual soil

almost doesn’t matter; the main thing is

an inner restitution, a purchase come by.

By Pacing it in words that make you feel

you’ve found your feet.. . .

or

the threshing scene in Tess of the D’Urbervilles—

That magnified my soul.

and also

Michael Collins, ambushed. . .

Has nothing to hold onto and falls again

Willingly, lastly, foreknowledgeably deep

Into the hay floor that gave once in his childhood

. . .

True or not, the fall within his fall,

. . .lets him find his feet

In an underworld of understanding

Better than any newsreel lying-in-state. . .

could ever manage to.

Or so

it can stated

in the must and drift of talk aabout the loose box.

I thought

Fred Marchant must have found his own feet in that poem. He read a three part

poem from his own Looking Glass House, “The Custody of Eyes.” In it he, too, seemed

to be finding his rhythm in meditating on three diverse sources: surrealist

art, a surreal sculpture, a piece of extraordinary hagiography on St. Agnes and

a visit to a sister in an asylum. My favorite section, “The Origins of the

Practice,” described the excruciating

tormenting of St. Agnes, \ by the crowd of onlookers, soldiers. The issue is

eyes that “are naturally unruly, straying without conscience,” A judge

orders Agnes stripped before a crowd.

There is a miracle, except for the suitor, no one looks at her

nakedness.

What is so interesting about this

poem is its evocation of concentration and the temptation to stray from it.

Straying from the concentration is straying from precise individuation of the

moment, the self, that is poetry. And

yet, that tension between attention and distraction is just the drama that gets

played out over and over again, bringing us back to the “tightness and

nilness,”the dangers and pleasure of “The Frontier of Writing.” Seamus Heaney.