|

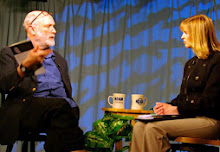

| Lawrence Ferlinghetti |

**** Years ago the late poet Jack Powers invited me to a lunch with poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti founder of City Lights Books. I had to work that day--and I regret that I didn't call in sick. Fortunately Steve Glines, the designer for the Ibbetson Street Press had dinner with the grand old man, and here is his story...

My Dinner with Larry

It was in the mid 1990's, Jack

Powers called to invite me over for dinner. Jack didn't drive so I took an

invitation like this to be an invitation to drive him all over town. Jack was a

lousy cook. His specialite de maison was spaghetti drenched with oil

covered tuna, beans, chili and a few more unappetizing components. I politely

declined. Jack insisted, promising dinner in a real North End restaurant, with

a celebrity.

Jack was the kind of person who

knew everyone in his tiny universe. He was a celebrity in his own right, but

only in the poetry community of Boston. Not a very big world as far as

celebrities go. Still whenever a big name poet came to town to give a well-paid

lecture or reading at one of the universities, they would always pay a visit to

Jack and occasionally read at his venue, the venerable “Stone Soup Poets.”

“Is it

anyone I know?” I asked.

“His name is

Larry.”

I could hear laughter in the

background and someone said, “He's the light of the city.” Still more laughter.

I thought I knew who the mystery

celebrity was. “I'll be there in an hour.”

I had known Jack for over 30 years.

When I first moved to Boston in 1970 I hung around the Grolier Bookshop where I

sit in an overstuffed chair and read for hours. In 1970 Harvard Square was full

of literary-want-to-be's, poseurs, for whom being thought of as a writer was

far more important than actually being a writer. I mentioned this to Gordon

Carnie, owner of the Grolier, who expressed a dislike for most of his

clientele, those same poseurs for whom being seen at the Grolier and

acknowledged by Gordon was the apex of their status. Gordon suggested I try the

Stone Soup Poetry in Boston. You'll find real poets there, he said.

I went to Stone Soup off and on for

the next forty years. I became a regular in the 1990's when my daughters

expressed an interest in poetry and literature. My youngest daughter made it

her mission to catalog the thousands of poems Jack had written over the

years. She gave up after cataloging well over a thousand items in just one

pile in one corner of just one room. The poems were written on the back of

envelopes, utility bills, shreds of Newspapers, etc. Each item was carefully

placed in a plastic bag, numbered and accompanied by a 3 x 5 index card stating

what it was, when it was written (if Jack could remember) and any other

interesting information. A duplicate card went into a file box.

As I was walking to Jack’s

apartment in Boston's North End I saw him carrying a dozen loaves of bread from

a truck to a restaurant. He went back and forth supplying every restaurant on

the block with fresh bread. The North End is very crowded and a delivery truck

stopped to deliver anything can be the cause of a major traffic jam. With Jack

doing the delivery the truck didn't have to stop for long. That was Jack's

explanation as we walked to his apartment.

When we got to the apartment there

was a young couple that had hitchhiked to Boston and Jack had taken them in ,and a bearded old

man with a red beret sitting in a very old, third hand, overstuffed chair, likely

saved from a trash heap. The old man got up and Jack introduced us. It was

Lawrence Ferlinghetti. “Call me Larry,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. I

have a photograph, someplace, that I took of the occasion. Its got everyone in

it but me, of course.

Jack lead us around the corner to an Italian

restaurant where Jack was acknowledged to be the celebrity of the

moment. We were lead to a private room. I sat next to Larry but I could never

bring myself to call him that. The two young kids were enthralled by Jack. I

don't know if they even knew who Lawrence Ferlinghetti was.

I love poetry and I

love history and, sometimes, I can talk intelligently about both but I am not a

scholar. Talking about poetry with Lawrence Ferlinghetti required at least

three large glasses of Italian red wine before I dared to bring up the subject

and voice an opinion. Before that point was reached, however, we talked about

his time in the U.S. Navy during WWII. His first assignment was on a yacht

re-purposed as a sub-chaser. A few short lived assignments and he was put in

command of a Destroyer Escort (DE). These clumsy little vessels could steam at

twelve knots, fifteen if they had to, while the convoy they were protecting

sailed along at eight to ten knots. Of

course, they had a five inch gun on the fore deck but without continuous target

practice there was little chance of hitting a target as small as a surfaced

submarine. His ship wasn't equipped with depth charges because it wasn't fast

enough to drop them and get out of the way of the resulting explosion. They

would have been hoist on their own petard. But the real purpose of the DE,

Ferlinghetti concluded was to take a hit from a torpedo launched by a German

sub to protect the convoy. On D-Day his ship was part of the anti-submarine

screen. Ironically, Ferlinghetti never fired a shot in anger and was never

fired at, as far as he knew.

Three large drinks

later we were ready to tackle poetry. We rambled around various topics until we

came to Haiku. Ferlinghetti claimed that we misunderstood it in the West. He

said it was a lot more than just a three-line poem with seventeen syllables,

written in a 5/7/5 syllable form. Indeed it could be any number of syllables as

long as it kept to the Hegelian, point, counterpoint, exclamation model. As an

example he offered:

Look, a cloud.

No, a flock of

birds.

Wow!

After a mildly

heated debate, and several more glasses of wine, Ferlinghetti admitted that he

had made it up. Then, with a gleam in his eye he announced that he had just

invented a new form of poetry: American Haiku.

For the next few

months I wrote dozens of bad American Haiku, every one of them read at Stone

Soup.

A bed of wet leaves

on solid rock?

Lookout, Ouch!

Frogs in the pond

bad news for bugs

Slap, not bad

enough

You get the

picture.