With Doug Holder

Poet Jennifer Martelli sees her life as

an "Uncanny Valley"- a term she told me that is used to describe the fact that what seems

right doesn't always feel right.-- thus the title of her new poetry

collection “ The Uncanny Value” ( Big Table Books).

Jennifer Martelli is the recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant in Poetry, and has been nominated for Pushcart and Best of the Net Awards. She’s taught high school English and women’s literature at Emerson College. She’s an associate editor for The Compassion Project: An Anthology, and lives in Marblehead, Massachusetts with her family.

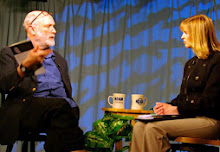

I had the privilege to speak to her on my Somerville Community Access TV program " Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer."

Jennifer Martelli is the recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant in Poetry, and has been nominated for Pushcart and Best of the Net Awards. She’s taught high school English and women’s literature at Emerson College. She’s an associate editor for The Compassion Project: An Anthology, and lives in Marblehead, Massachusetts with her family.

I had the privilege to speak to her on my Somerville Community Access TV program " Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer."

Doug Holder: You have said in an

interview that you write in the plainest language possible. So you

have no problem with accessible poetry?

Jennifer Martelli: No—not at all.

Early on this was a problem. So many professors would say that my

writing is so beautiful, but they didn't understand what it is about.

There was a part of me that felt-- for poetry to be deep or important

it had to be inaccessible in a way. So half the time I didn't

understand what I was trying to say. Eventually I went the other way.

I tried to just tell a story. I learned that from Marie Howe. Now I

am coming back to the middle, a little. I am trying to balance

heightened language that is beautiful—with some artifice. But first

I want to communicate with people. It is a razor's edge sometimes.

DH: You also mentioned in the interview

that Elizabeth Bishop, Marie Howe, and,Sylvia Plath have influenced

you. What is the common thread among these poets that attracts you?

JM: First off they are strong female

poets. There is a strong female voice. Over the past six months if I

bought a poetry book it was written by a woman. I didn't start this

consciously. I love male poets too, of course. I love Robert Haas,

Thomas Lux-- with his brilliant short lines, and Tony Hoagland—he was a

teacher of mine—probably the smartest man I know. The women poets I

mentioned are all different—but again I am attracted to them. What

I love about Bishop—Bishop is talking to you in her poems. Like in

“ One Art” she is making discoveries in the poem, and she is

surprised in the poem.

DH: You studied at Boston University as

an undergraduate, and you got your MFA from Warren Wilson. Who were

some of the folks of note you studied with?

JM: You know—when I lived in

Cambridge, Mass.-- you could more or less create your own MFA without

entering a program. Major poets were living in Cambridge and for as

little as a 100 dollars you could opt in. I remember folks like

Steven Cramer and Robert Haas had workshops that folks could attend.

When I was at Warren Wilson a big influence on me was Ellen Bryant

Voight—she is a brilliant woman. Her notes were wonderful. Before

the Internet took hold we wrote each other letters. tThe letters I

have from her are like a textbook.

DH: You are the associate editor for

the Compassion Anthology. Tell us about this and your role there.

JM: This is really Laurette Folk's

baby. Laurette is a jack of many trades. She is a writer, novelist,

and visual artist. She created this anthology online. What she wants

to do is to bring compassion through action.-- like creating art

and poetry. I am a poetry reader for the project. I give my input. We

are starting to see amazing poets and poetry being contributed to the

anthology.

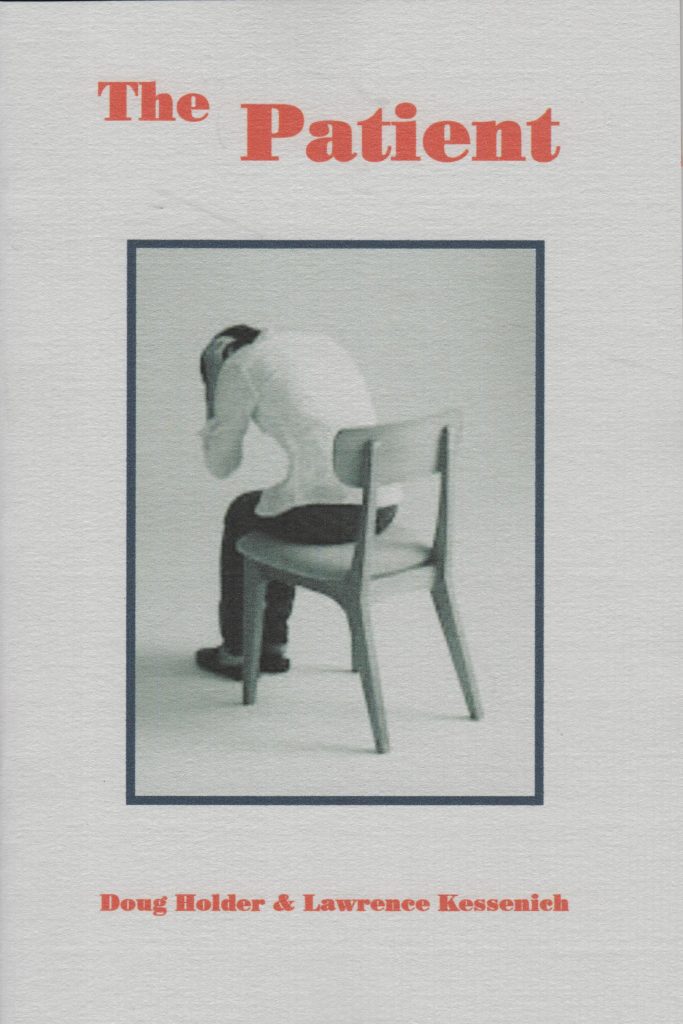

DH: Your new collection is “ The

Uncanny Valley” ( Big Table Books). Tell us about the germ of the

idea for this poetry book.

JM: It is essentially biographical. It

is about growing up in Revere, Mass.to my life now-- in middle-age.

It covers marriage, love, and writing. It deals with how one

navigates one's way in the world. I find it inevitably hard. Robin

Stratton, my publisher and editor, steered me to discover a great

title. An “Uncanny Valley” is a term in aesthetics that describes

things that look right but don't feel right. That describes my 54

years on this earth.

DH: In the collection you have a great

poem titled: “Devil Tide.” You describe this group of nefarious

unforgiving rocks, the laments of seagulls, as a metaphor for how we

cut ourselves off from people.

JM: That poem—is a prose poem. It is

a conglomerate of the many beaches I visited and lived near. I have

always lived near a beach. I have lived in Marblehead, Gloucester,

and Lynn. The poem has to do to with how to say goodbye to people who

might be dead or not in your life anymore. All these images came

together for me and the poem was birthed.

DH: Was there a literary community in

Revere where you grew up? I know poet Kevin Carey was born there and

the novelist Roland Merullo.

JM: There was no real literary

community. It truly was a working-class city. My parents grew up

during the Depression and they felt poetry was frivolous. There were

really not many places to go with my interest, aside from English

class. If you look at Carey's work and Merullo's you'll see what I

mean.

The

Devil Tides

There

are rocks off the coast shaped like eggs. There are rocks shaped like

misery and one like a skull. Bodies have washed up on the slippery

barnacles at low tide. There is a brown island I can walk to from the

crushed shell beach. If you are born up here, you know sadness and

you know gulls. You know how a good clamshell makes a good ashtray.

You know the land is as flat as any place where men change into

wolves under the mutton moon. You know that. Resent everything, for

it’s the only way you don’t forget. Resent everything you love,

it keeps you anchored to the beach. Fishing boats bring in cargo from

pink and white tulip fields in the Orient. The heroin is cheap and

it is hot. Just past King’s Beach the seaweed is red clogged with

pennies or fingers. It smells even in the cold. Too many villages

are connected by thin causeways pinched on either side by the

Atlantic. Devil tides cut them off from the world. Folks go out and

never come back. There are empty graves engraved in marble in big

churches. Folks go out hot and turn blue. No one ever forgets,

except how to measure. If you knew this, you’d never ask anything

more of me.