Thursday, February 15, 2018

Susan Tepper Interviews author Alex M. Pruteanu

Susan Tepper Interviews author Alex M. Pruteanu

Susan Tepper: Every book of note that I’ve ever read has one line that cements the heart of the story. In your new novel The Sun Eaters it is this line:

Everything that was alive was hungry, always.

Alex M. Pruteanu: I can certainly speak to that. Hunger gives a certain kind of clarity and awareness of everything around you. The senses, all of them, are almost working overtime. You’re ultra-aware of your biology and how it’s changed, of your digestive system in particular.

To get back to this idea that everything that was alive was hungry, always. If you look around at whatever is left of nature, you’ll see that every animal is engaged actively and aggressively in finding food. Everything about an animal’s life from the time it opens its eyes involves hunting/gathering/scavenging for food. It’s daily warfare. Finding food is what they all do every day of their lives.

ST: And, conversely, warfare brings hunger to those who manage to stay alive.

In the narrative you wrote:

Our hunger was chronic… Every spring we would forage for dandelions and nettles. Dandelions were bitter in the summer and autumn, but if we plucked them while they were young, in the spring, they had a sweeter taste… We ate everything from the flower all the way down to the root… Nettles were tricky… Their leaves bit back…

AP: I thought about the immense difficulty a person has to face if he or she is engaged in the never-ending battle of finding food on a daily basis. Food that doesn’t exist or isn’t much available. Imagine living a life like that. Being in competition with not just your fellow humans, but every living thing around you, every animal, to merely find food for the day.

ST: I’ve read tidbits about your own life, from time to time, in other interviews. I know you were born in Romania and emigrated to the states at some point. Can you tell us how your origins helped craft The Sun Eaters.

AP: I was born in Bucharest, Romania in 1969. My mom defected to the States in 1979 and after close to a year of working to obtain our passports, my father and I were let out of the country to come join my mom here as political refugees. I arrived in the States in late January, 1980.

ST: You were eleven years old. How did it feel to leave your homeland? Was it easy for a boy just entering puberty to connect with American kids?

AP: It felt wrong to leave, initially, and beyond. I was basically told that we were leaving, not asked. And I was kept in the dark about the plan of my mother's defection, so it came suddenly for me. As I knew it, she had taken a trip to the United States as part of an economic delegation, and she never returned. In Romania, I had social connections and a lot of friends that I was told I'd have to leave behind. Plus, from the time my father applied to have our passports released and get permission to leave the country for good, I became sort of a cancer. People didn't much feel like being associated with both my father and I. Everyone was being watched/monitored by the secret police, so being associated with someone who was applying to leave for good and join a person who had defected— which officially meant that treason was committed by the defector— was not in the best interest of those staying behind.

ST: It must have been terribly strange and stressful for a child.

AP: When it became official that my father and I were trying to leave the country, my friends backed off. It was a strange period. At one point, I didn't even have to go to school. As I remember it, I went anyway, but I wasn't really part of the class anymore. I wasn't given tests or projects to complete. I didn't get any more grades on anything. I would just go and sit in class. It was all surreal.

ST: Extremely. There are points in The Sun Eaters that are also quite surreal. The two brothers live with their mother in a decimated Eastern European village populated by women doing the labors of men. The men, including their Da, have gone to war and not come back. An exchange between the older brother, Vladi, and their mother begins:

“I dreamed of bird-fish, Ma. They howled and wailed and whistled hot flames from their lips. There were so many it got dark. I couldn’t see.”

“Those are airplanes, Vladi. Don’t be scared. Come to me.”

This dialogue, I believe, is unconsciously lifted, part and parcel, from your own uncertain path as a child who was forced to leave home and country.

AP: Probably. I recall vividly the times I spent (vacations/holidays) at my paternal and maternal grandparents’ homes, which were both in villages in the countryside, although my maternal grandfather had a country house, but just on the outskirts of Ploesti—a town that was bombed by the Allies in WWII due to its several working oilfields (for some time during WWII Romania was allied with Germany).

ST: Perhaps that is what stirred up the section of the book that concerns their visit to the enigmatic and mysterious Uncle Miki who does have food and other luxuries.

Your narrator tells us:

Because of its oil fields and refineries, Uncle Miki’s city was under siege nearly the entire duration of the war… bombed from above by bird-fish every day, so Uncle became part of an invisible force of resistance… Vladi said he was a resistance administrator… he would shuttle very important papers sewn in the lining of his coat…

Secret agents, another dark unfolding in the plight of humankind.

AP: A lot of material in the novel is written from recollections of “adventures” I had as a young boy with friends I had made during my times spent in the countryside. As I recall, one of the toughest inconveniences was having to use an outhouse quite some ways away from the house, and in winter. Winters in Romania are notoriously tough; the country lies on the same parallel as Montreal, Canada. But having to get up in the middle of the night to use the outhouse in the dead of winter was particularly brutal. We also didn’t have running water, so bathing was not a pleasant experience, even though the water—brought in large pails from the well by my grandparents—was boiled on the wood stove first, before being dumped into a wooden tub. Other events in the book I simply made up. Some parts are influenced by stories I’ve heard from village friends, and some are re-imagined and re-told from stories my father recounted about his own life with his brother in the village of Blagesti, in northeastern Romania. It’s all spun into fiction.

ST: The Sun Eaters is a brilliant and intensely readable novel that deals with hardship and extreme resiliency when faced with the devastating realities of life after war. Whether or not deliberate on the part of its author, this story stretches well beyond, sifting into the political environment of hunger and deprivations the world is facing now.

******Susan Tepper is the author of seven books of fiction and poetry. Her latest title 'Monte Carlo Days & Nights' (Rain Mountain Press, NYC) is a novella set on the French Riviera. More at www.susantepper.com

Tuesday, February 13, 2018

The Contrarian Voice and other poems by Ernest Hebert

The Contrarian Voice

and other poems

by Ernest Hebert

Bauhan Publishing

P. O. Box 117

Peterborough, NH 03458

ISBN9780872332485

What a pleasure to pick up a book of poems and find myself well

into it without once halting in puzzlement, encountering poems clothed in

obscurities of diction, syntax and metaphor. Poems that seem designed to make you

feel as if the appreciation of poetry requires membership in a cult of superior

sensibility, from which you, philistine, are excluded for your unfashionable

taste. I feel that such poems, like the emperor, have no clothes, while these

poems of Ernest Hebert are made of solid, worn from labor, denim, because, from

the beginning lines of the book,

I loved what I could compare to

what I loved.

The surface of a pond is slightly

curved

as is music from a violin and the

violin itself.

as I tried them on, one after another, they fit.

Twenty minutes later, when I finished the first of the

book’s four sections, “Septuagenarian Look-Back,” I felt that Ernest Hebert deserves

as much attention as Billy Collins. His poetry shares a sardonic perspective

with Collins. Here is “The Dogs of Tunapuna, Trinidad” from this section in

support of my thesis:

The streets are full of them,

big-balled dogs with torn up flanks

and limping bitches with prominent

tits.

They sleep the day and roam the

night

to mate, quarrel, and carry on.

for a couple of hours you hear

only an occasional bark or yelp,

then all of a sudden half a dozen

will start in.

Soon the entire island is howling.

It all sounds comic,

until you realize that these

creatures

are killing and maiming one another

over useless territory and loveless

fucking,

just like the rest of us,

a response to evolution,

spittle from the God Roar.

The last three words of that poem reappear in the long title

for the second section: “Poems Inspired by, The

God Roar (a novel I never wrote, which in turn was inspired by a sculpture

by Brenda Garand.)” The section begins with “Hypothermia,” when “I” discovers “You”

in a snowdrift, near death from the cold. “I” rescues “You” and undresses “You’s”

unconscious body and warms it with his and “You” recovers as they share his

sleeping bag and have this conversation:

"Come to consciousness, I

said.

"Do I know you?" You

said.

"I hardly know myself," I

said.

We lay quiet and still for an hour,

then I asked why you came into

these woods.

You said, "Listen."

"I don't hear anything."

"Yes you do – listen."

"I hear it now,

the tick and scrape of tree

branches."

"How nice when the wind blows

through the tops

of the trees and underneath it's

still."

"You came for that, a

sound?"

"Yes, the God Roar, to record

it for posterity.

…”

However, the possibility of intimacy contained in this

beginning remains unfulfilled in the seven poems of this section that are the

fragments of a strange and dreamlike story told by "I." The plot elements

sketched in these poems left me intrigued but dissatisfied. They are analogous

to Sargent’s studies for the murals in the rotunda of Boston’s MFA, which are engaging

in reference to the complete work, but of marginal interest without it.

Fortunately, with the third section, “Poems and Songs in the

Darby Chronicles,” Hebert is back in full voiced empathy for the Yankees and

French Canadians who worked in the mills and were abandoned when Capital moved

their work south to our Free Trade Zone with the Carolinas. The “Darby

Chronicles” are a series of seven novels Hebert has written about a fictional New

Hampshire town and the inhabitants of the surrounding hills; each poem in this

section is attributed to a character in one of those novels. This one,

“Untitled,” is belongs to Hadly Blue in A

Little More than Kin:

This sea in her gift for

composition

has made a place, if not self,

for that rock, that kelp.

Thus I am unconcerned

that my hat has blown away,

that the gulls are laughing:

"There is less of him than

usual."

By the fourth section, "Howard Elman: An Old Working

Man's Meditations," the sardonic humor of Septuagenarian that is the

muscle in the voice of the first section has matured by 10 years:

Plow Guy's Lament

…[four lines]

Octogenarian walked over to the

truck.

Junior rolled down the window.

"How come you, not your

dad?"

"He bought the farm

yesterday,"

Junior said, just as calmly

as one talking about the weather.

…[14 lines]

Junior's only emotion

at the moment was glee

at the thought of inheriting

an almost new truck.

The grief would come later.

The concluding and title poem of the volume, "The

Contrarian Voice," that follows, begins as Elman, now a widower, gives us

a catalog of grieves that for him came later:

Munch on a village store grinder

while you imagine Wife

standing at the sink

and gazing out the window

at her birdfeeder,

just as she had done in life.

Tell her how sad you are:

connections and conniption fits

that enriched your life,

the Centenarian’s stew pot,

involuntarily memorized glimpses

of trees, stone walls, ledges,

old mossy gravestones,

fences and hosses and cows

…

This poem of 309 lines is a collection of more catalogs;

some are angry; some are nostalgic (and of those some are regretful); and some

are playful and speculative, as when he sends an email to his Sane Daughter:

Saint Peter, cranky gatekeeper of

Catholic heaven

and frequent lurker on the

Internet,

intercepts message to Sane

Daughter.

Checks it off as a venial sin

and files it in the database.

Saint Peter is tired. This job is a

lot of work.

Slips a note in the Judgment Day

Suggestion Box:

How

about an honorable mention

for

the lab mice who did more

for

the species who enslaved them

than

the species did for themselves?

This introduction of Saint Peter is followed by a catalog of

possible ways that Elman might die framed as an argument with himself. At its

conclusion, “You don't have a prayer./‘I don't have a prayer,” Hebert

reintroduces Saint Peter to answer Elman's assumption of damnation with one

final catalog, which suggests that redemption will be granted to Elman and to

all working stiffs just for the virtue of their being working class:

You don’t have a prayer.

I don’t have a prayer.

Saint Peter doesn't have a prayer,

so he checks the historical record,

bumps his forehead with his palm,

and calls out in Octogenarian’s

voice,

talking in his sleep,

“Jesus, I get it now:

the ones with no education,

the ones who made mistakes in youth

and paid for them over a lifetime,

the ones who built the idiot

pyramids,

and the useless cathedrals,

and that stupid wall in China,

…[seven lines]

and who appeared in apparitions in

the minds

of soldiers calling for their

mothers

as they lay bleeding out on the

battlefield,

and who fucked the bosses to save

us all –

they are all fucked.

And fucked again.

And fucked over.

And fucked forever,

us, the working people.”

After speaking this I think Peter should exchange his mythic

robes of white silk for working ones of denim, faded from hard use and many washings.

--

Wendell Smith

Sunday, February 11, 2018

Tenth anniversary of the 2008 Dylan Thomas Tribute Tour of America

|

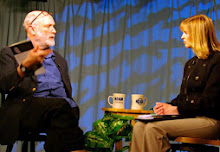

| Peter Thabit Jones/Aeronwy Thomas |

On

the tenth anniversary of the 2008 Dylan Thomas Tribute Tour of

America, featuring Aeronwy Thomas, his daughter, and Swansea poet and

dramatist Peter Thabit Jones, a commemorative book will be published

by The Seventh Quarry Press, UK, and Cross-Cultural Communications,

USA.

The

Tour, which was organized by Peter’s and Aeronwy’s American

publisher Stanley H. Barkan, in consultation with poet and emeritus

professor Vince Clemente of New York, saw Aeronwy and Peter travel

from New York to California, whilst taking in many other states and

reading at prestigious venues, such as the National Arts Club, New

York, the Chrysler Building, which was then the home of the Welsh

Government in New York, the Walt Whitman Birthplace, Knox College,

Illinois, and the Monterey Peninsular College in California. At the

end of the Tour, Peter and Aeronwy were commissioned by Catrin Brace

of the Welsh Government in New York to write the first-ever Dylan

Thomas Walking Tour of Greewnich Village,

which is now available as a pocket-book, a smartphone app, which was

developed especially for the 2014 Dylan Thomas Centenary, and a

guided tour by New York Fun Tours.

The

forthcoming book, entitled America,

Aeronwy, and Me/Dylan Thomas Tribute Tour of America,

which is being edited by Peter Thabit Jones will contain the Tour

schedule, prose memories by Peter of each event they did and other

prose memories, some poems by Aeronwy and Peter inspired by America,

relevant Tour photos, and contributions from those who hosted them at

universities and venues across America.

Stanley

H. Barkan will write the Preface to the book, which will be in

memory of Aeronwy who died in 2009. The book, which will be published

this autumn, has had the blessing of the family of Aeronwy Thomas.

Peter

Thabit Jones

Author,

with Aeronwy Thomas, of the

Dylan Thomas Walking Tour of Greenwich Village

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)